[Part 1/3] [Part 2/3]

Introducing WWI by working with photographs

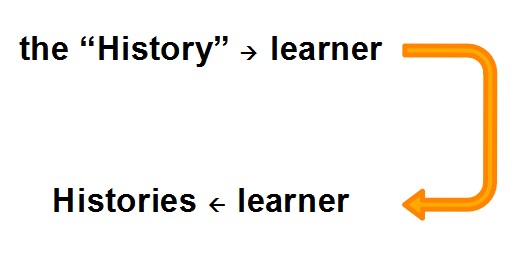

Students never come to class as „blank sheets“. They always have heard or read something about the topics the curriculum is proposing. They have their own concepts to explain the world around them, including history. Working this way allows teachers to get to know these pre-concepts and to adjust contents, methods and materials to the needs of each learning group.

Before you start talking about World War One in your history lessons, you will give the students the links to the Europeana photo collection. Ask them to choose one photo representing World War One for them. After some minutes of research in the collections, the students present their findings and explain to the others why they have chosen the photo. By this, you will get to know their pre-concepts, ideas and beliefs about World War One. At the end of the teaching unit on the First World War, students look again at their photo from the beginning and they are asked if they chose now the same photo as representation of WWI. Thereby, you will see if there were conceptual changes after having discussed several aspects of WWI in the past lessons. The students’s explanations may serve you as indicator for the quality of the past lessons.

You can use the same idea in a bit more complexe way by letting the students work in small groups creating collages of several photos (fix the number, it should not be equal to the number of students in a group). The advantage is that there will be less presentations. The approach in itself is more dynamic because from the very beginning the students have to discuss about the choice of the pictures – so they already start comparing and adjusting their pre-concepts on the topic. In the end of the teaching unit you can use it in the same way asking if they kept the same pictures or not after what they have learned about World War One in school.

Curate a virtual exhibition

Usually, the history curriculum prescribes to treat different aspects of World War One in the classroom. Obviously, there are differences from country to country. However in general, these are aspects like the war in the trenches, woman in World War One, Propaganda or the Home Front. If you take a look at the Europeana collections you see quickly that the sources are already structured around such topics, called “subjects” in the Europeana. With additional materials like the corresponding chapters in the textbook, students can be asked to choose between one of the topics demanded by the curriculum, eventually they can also propose additional ones as long as the obligatory topics are covered.

Students work in small groups, gathering and exploiting information with the final task to curate a virtual exhibition on their topic using pieces from the Europeana collections. It can be helpful to restrict the number of objects to 5 or 10 (of course, limited space as a reason seems less relevant online than in a museum – nevertheless this is real life task). That way students have to discuss the choice of objects and develop criteria for their presentation. In addition, like in a museum, they have to write short texts to explain the objects in exhibition, in order that their classmates are able to use their exhibition to learn about this aspect of the war without further information. It is important that all students have the time to see the results of the other groups, to discuss and evaluate the different exhibitions with regard to previously defined criteria on their quality.

Working with film sources

The Europeana collections 1914-1918 contain also digitised film sources from several European archives and institutions. Students love films. Not only watching them but also making videos. This is the generation of youtube we are working with in schools.

And in fact, in every class you will find some pupils who are quite handy and experienced in making videos. Some even have their own youtube channel. As a teacher, it is absolutely not necessary to be a perfect filmmaker. You only has to check if the students are interested in making their own videos and if there are enough of them to help and support their fellow students in group work.

If so, what can you do with the moving images from 1914 or 1918? Well, first you can watch and analyse them. That is not too exciting, though some general ideas of film analysis, camera positions etc. are absolutely essential for any work in which students start creating their own videos.

A technically very easy idea to work with these videos in the classroom is to let students do some research and on this base, let them write and record an audio commentary to one of the films. If this seems to easy for you, students can write their commentary from a defined (historical or current) perspective.

In a more sophisticated approach, students use these films, cut off scenes and remix them to create their own documentary on World War One. Of course, this needs already a lot of practice and quite a good knowledge about propaganda, perspectives and different use of images. It is certainly rather a kind of project for upper grade students. The results do not have to be as perfect as what students can see everyday on television or youtube. However, I have made the experience that some pupils get quite ambitious to create an excellent product. In any case, this activity promotes a deeper understanding of how TV documentaries are made, how they work and how manipulation is possible. After this teaching unit, students will look differently, certainly much more critical, at the products of visual history we are all surrounded by.